How It Sounds

Sometimes it’s the offhand comments that tell you the most.

In a conversation a few days ago, some thoughtful faculty noted in passing that the state’s constant drumbeat about job placement and STEM fields — two different things, btw — was becoming a factor in faculty morale in the humanities and social sciences. They heard every invocation of college-as-personnel-office as an attack on what they do, and as a harbinger of even-more-diminished resources to come.

I couldn’t blame them, really. Budgets are tight, new state and federal money (when it exists) tends to go to more favored areas, and it’s not hard to read the public mood.

As someone who has attended more Employer Advisory Boards than is probably healthy, I can attest that much of the “;practical-versus-pure” dichotomy is overdrawn, if not simply false. But the political rhetoric is pushing in one direction, so some folks — understandably, if unhelpfully — are compelled to push back in the other, thereby implying that the terms of the discussion are correct. If I could, I’d love to convene some much larger Employer Advisory Boards and invite both politicians and the English department to observe silently.

Even in our most baldly vocational programs, employers consistently make it clear that their greatest need, and disappointment, with new employees is with the soft skills. Even in technical areas, we hear consistently that anyone who wants to move above the entry level needs to have good communication skills, good workplace savvy, and a basic sense of numeracy. The employers are still willing to do a certain amount of training on their own specific systems; what they want from us is people are who have the skills to be trainable and employable.

In their more thoughtful moments, I’ve heard politicians acknowledge that. But in the heat of legislative battle, such counterintuitive truths don’t get heard. Instead, we fall into stereotypes of “;ivory tower” academics not preparing students for the “;real world,” and we believe somehow that if we could just reduce education to training, everything would be fine.

It doesn’t work like that. It has never worked like that.

The relevant question is not whether we should fund, say, chemistry, as opposed to sociology. (Last week, the Freakonomics folks — whose readers tend to have economics backgrounds — did a poll asking which social sciences should die. Shockingly, economists didn’t choose economics.) That’s the wrong question at the systemic level. (It can be the right question on individual campuses, but that’s another issue.) Both majors can produce thoughtful people who have something to offer, and both can produce drones. And especially in the first two years of college, it makes sense for students to have at least some exposure to each discipline, or at least to similar ones.

At its core, some very smart economists say, the jobs crisis is not primarily about having too many sociology majors. It’s about having a too-skewed distribution of wealth, a too-powerful financial services industry, and too many people making life choices that any competent sociologist could tell you don’t lead to good outcomes. I’m much more worried about college dropouts — especially those with heavy loan payments — than I am about graduates with degrees in comparative literature.

Historically, the liberal arts grads have struggled somewhat to get the first real job, but have done quite well for themselves once they’ve made their way in. They just need that first foot in the door, which is a tall order during a nasty recession. But let’s not confuse the effects of the nasty recession with the value of the liberal arts education. And even more importantly, let’s not make the mistake of purging the “;gen ed” courses from the technical and vocational fields. Technical firms need managers too, and those managers will need to be able to understand people, write and speak well, and make decisions with limited and flawed information.

Attacking the humanists is not going to solve the recession. It simply is not. If the employers with whom I speak are to be believed, that’s the last thing we should do. Short-term training is, at best, a short-term solution; if we really want long-term prosperity, we need people who bring the whole package. That means recognizing English and history and, yes, sociology as integral parts of our mission. The answer isn’t to hit back with the virtues of irrelevance; it’s to affirm the relevance of the educational core. We need people who know enough to listen to the offhand remarks.

Thinking about Coursera’s Growth

The online education platform Coursera announced today that 12 more universities had signed on as partners, joining the 4 that were part of the startup’s launch in April. Joining the University of Pennsylvania, Princeton, University of Michigan and Stanford are Georgia Tech, Duke University, University of Washington, Caltech, Rice University, University of Edinburgh, University of Toronto, EPFL – Lausanne (Switzerland), Johns Hopkins University (School of Public Health), UCSF, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and the University of Virginia.

That last university is a particularly interesting one, considering the role that MOOCs played in the ouster of UVA president Teresa Sullivan by its Board of Visitors. The decision-making at UVA is the focus of much of Inside Higher Ed’s Steve Kolowich’s article on today’s news. Kolowich chronicles the negotiations among UVA deans, faculty members and Coursera, noting the irony that these discussions were ongoing as the BOV fired Sullivan for failing to have an adequate response to their questions about the university’s plans to respond to the Stanford-model MOOCs. The plans are clear now: join the Coursera platform.

The rapid expansion of Coursera’s partners, along with the equity investment made by two of them, certainly suggests that many institutions are preparing to face what the New York Times’ David Brooks called the “;campus tsunami.” Initially, Coursera had to woo schools and professors; now schools and professors are approaching Coursera, which offers universities its technology and expertise in teaching and grading “;at scale.” And while this might demonstrate what Coursera co-founder Andrew Ng told me -; that “;MOOCs are not a passing fad” -; it’s not clear yet how MOOCs will evolve as they expand to new disciplines and new universities and/or how these MOOCs will change higher education in turn.

It’s the latter that seems to elicit the most excitement and concern. Georgia Tech computer science professor Mark Guzdial has shared the email that faculty received there announcing its partnership with Coursera. In it, Provost Rafael Bras offers reassurance that “;we are not abandoning our central mission of residential undergraduate instruction. In fact, we view this as an opportunity to remain true to our pledge to define the technological research university of the 21st century by exploring new modes of instruction and operation. What we learn from the Coursera and other similar experiments will above all benefit our own students and strengthen our existing programs.”

That echoes how Ng and his co-founder Daphne Koller describe Coursera as creating a “;better education for everyone.” When I spoke to the duo when Coursera launched, Koller said that the creation of these online courses will make for robust and active learning experiences on campus. There is a “;growing amount of content out there on the Web,” she said, and “;the value proposition for the university isn’t getting the content out there but rather the personal interaction between faculty and students and students and students.”

That is part of the value proposition of the residential campus experience, I’d argue. When I asked Ng about the impetus behind these universities’ signing up for Coursera, he said that both faculty and administration were pushing for it. But students at these universities, not so much. That’s not to say that students in general aren’t interested in the free online classes -; Coursera boasts 1.5 million course enrollments by over 680,000 students. But these students aren’t necessarily that same population served by a residential campus. (According to demographics from Ng’s Machine Learning class offered last fall, only about 11% were in undergraduate degree programs.) In The New York Times today, University of Michigan (and Coursera) professor Scott Page says, “;There’s talk about how online education’s going to wipe out universities, but a lot of what we do on campus is help people transition from 18 to 22, and that is a complicated thing,.” He adds that MOOCs would be most helpful to “;people 22 to 102, international students and smart retired people.”

Who’s being “;helped” here is a crucial consideration -; for institutions, for faculty (both research and instructional faculty), for enrolled students and for learners everywhere.

A few lingering questions:

- How will the University of Washington’s plans to offer credit for its Coursera classes work? (And related: how will concerns about online cheating be addressed? Udacity partnered with Pearson for this.)

- How will a partnership with Coursera change universities’ other online course offerings? (These universities and other universities, pre-existing and planned programs, and particularly for-credit ones)

- How will the peer grading work? (History professor Jonathan Rees raises questions about how well students will be able to evaluate one another’s assignments.)

- With all these online lecture-based course options, whither the offline lecture-based course offerings? And how will funding models have to change for universities if students opt to learn “;elsewhere” for these credits?

Taking into consideration options

Recently, I was talking to a friend of the family. A middle-aged woman with a PhD, she's fluent in three languages and has spent a reasonable portion of her life in Europe.

One question that came up was why, in certain countries, people might be disallowed from spending their own money to buy health care that the relevant national health care system might deem to be unnecessary or of low priority.

The basic premise underlying that question, of course, is that people who have sufficient money should be able to spend it on anything they choose. It's a pretty common premise, particularly in this country. But it's not completely true.

When some function is seen as critical to the functioning of society, the application of money to advantage one individual over another is no longer seen as consumer choice, it's seen as corruption. People shouldn't be able to spend money to get better treatment from the justice system. They shouldn't be able to spend money (at least, not directly) to influence people when they're in the voting booth. And they shouldn't be able to buy legislation (again, at least not directly).

Physical security and equal treatment before the law is something a just society provides. Universal education is something a just (and wise, and capable) society provides. And, for the citizens of most developed countries, health care is something their society (just) provides. Some of those countries have decided that allowing private money (and private providers) to enter the health care market is as corrupting as allowing bribery of police or judges or legislators. As Hannah Arendt said, "Society is the form in which the fact of mutual dependence for the sake of life and nothing else assumes public significance." Health care would seem to qualify.

My concern is not that this woman (a US citizen) doesn't have universally-available health insurance. (Her husband is a federal retiree; health insurance isn't a problem for them.) Nor do I worry that, in spite of having traveled and lived extensively in countries with universal health care she still doesn't understand how it works or how it affects social dynamics. My concern is that she seems typical of so many Americans who appear unable to imagine any situation other than the one in which they currently find themselves. No health care finance system other than the one we have (except, perhaps, the one we had before the Affordable Care Act was passed). No education system other than the one we have. No legislative system other than the one we have. No military other than the one we have. No economic system other than the one we have.

Have we created a generation or three with no real sense of possibility? And if we (society) have, how much of the damage has been done by those of us in education?

six Approaches the iPhone Altered Larger Ed

This past Friday was the 5th anniversary of the launch of the iPhone. Over at the NYTimes Bits blog Brian Chen, author of Always On: How the iPhone Unlocked the Anything-Anytime-Anywhere Future — and Locked Us In, has some observations about how the iPhone changed phone and software industries.

The way to think about the iPhone in relation to higher ed is less as a single product but a new product category. This category, which includes Android/Google and maybe eventually the Windows 8 phones, equals smart phone plus an app ecosystem. The carriers (Verizon, Sprint, AT&T etc.) remain a critical (as they own the cellular network), but annoying component of this ecosystem. Annoying because their voice/data pricing plans are only getting more expensive, restrictive and confusing as the hardware and software on smartphones improves exponentially each year. Any impact that the iPhone and its cousins achieve in higher ed will be in spite of, rather than because, the big cellular companies that we all must endure.

How has the iPhone changed higher ed?

1. A Glimpse Into A Mobile Learning Future: The iPhone has allowed us to clearly peer in our learning future, and that future is mobile. The only limitation will be that processing power, storage and software will improve faster than our ability to re-engineer learning tools around the mobile form factor. What would an LMS (learning management system) designed from scratch for Apple's iOS and Google's Android look like? Can we imagine virtual synchronous classroom/meeting tools such as Adobe Connect and Blackboard Collaborate look like with a native mobile design?). The iPhone screen seems plenty big enough, the rate-limiting step of the iPhone as a learning platform seems to be the keyboard. Mobile devices are great for content consumption, not so wonderful for creation (and education depends on creation). Despite the challenges, it seems clear that the ubiquitousness nature (always with us, always connected) of the iPhone type device will make mobile the primary platform for 21st century learning. We are evolving to a place where our mobiles are extensions of ourselves, our outboard brains and always at hand communications and entertainment devices. Where gaming and social media and communication go, education will soon follow.

2. The Apps vs. Browser Debate: To a great and growing extent education is already mediated through technology. We interact with our fellow students, professors, and course content via software. This software is moving from our computers to our smart phones (and tablets). The question is, how what form will this software take? Will it be delivered through the browser or an app? Perhaps the browser/app debate will soon fade, as native apps become web apps – simple shells around browser based content and data exchange. The desire to avoid the expense and complication of coding separate apps for each platform (iOS, Android) and for the Web is understandable. I'm unconvinced, however, that this approach will provide us with high quality mobile (and mobile educational) experiences. The gold standard for apps in my experience is the NYTimes and Amazon Kindle iPhone app. These apps are easy to navigate, sync automatically, and work offline. Reading a book with the Kindle app or news through the NYTimes app causes the device to recede into the background. I don't know of any education app that performs as well as these two examples, and I have a hard time believing that when that app comes it will not be a native mobile app.

3. The Mobile Services Imperative: Every college and university feels the pressure to mobilize our web content. All the work we have done in the past 20 or so years to get our higher ed content and services to the web seems inadequate if this same content and services are not available for smart phones. Where we are going to get the resources to bring everything we do on the web to the mobile screen is a reasonable question. The web work will not go away (it will expand), and the pull to mobile will only get stronger. Will web sites designed with RWD (responsive web design) techniques be robust enough to perform on iPhones at the level that our students, faculty, staff, alumni, potential students expect? Can we avoid coding around native apps, and instead go with a write-once display everywhere web app strategy, allow us to move rapidly and cost-effectively enough into our mobile campus future?

4. Device Proliferation and Support Challenges: Campus technology services and campus applications now need to work with both computers and mobile devices. Do you have an easy way that your students, faculty and staff can get their iPhones on your secure wireless network, your printing and application authentication systems? What devices will you support in your student help desk? How far will you go to help your professors troubleshoot their mobile devices? What training, advice, and support will you offer instructors on incorporating mobile phones into teaching?

5. A BRIC Education Growth Roadmap: The BRICS are Brazil, Russia, India and China – they are the fast growing emerging economies with huge populations and a rapidly increasing role in global trade, manufacturing, services and consumption. We could (and should) spend lots of time thinking about the opportunity to export US higher education to the BRICS, and to grow the footprint of our educational technology and educational publishing companies in these countries. As the action in higher education moves from the already wealthy to the growth economies (the BRICs and beyond … such as South Korea, Turkey, Mexico, Indonesia, and Nigeria), the mediating technology will be the mobile device. The BRICS largely skipped over landline technology, jumping directly to cellular phones. The demand for educational services at every level will be way larger than traditional place based (campus based) institutions could ever provide. Education will be mobile. Campuses will still be built, but the great volume of educational interactions will take place on the mobile phone.

6. The Disappointment of Unrealized Mobile Education Potential: The final way that the iPhone has changed higher ed over the past 5 years is the degree to which the iPhone has not changed higher ed. The mobile education hype has outpaced the mobile education reality. Smart phone education applications and service continue to be an appendage to those designed for the web. We lag behind in delivering our students the course, library, and campus services and content that they want on their mobile devices. We have very little understanding of how we can incorporate these handheld mobile computers into our teaching. And from what I can tell, Apple, Google or Microsoft have not made education a core part of their long-term mobile strategies.

What would you add to this list of how the iPhone changed higher ed?

“Hear the students’ voices swelling. Powerful and true and clear. . .”

Myra Ann Houser is a doctoral candidate in African History at Howard University in Washington, DC. She blogs about the dissertation-writing process, current events, life in Washington, DC, and related issues at myraramblings.wordpress.com and tweets as @myramt.

In the spring of 2008 I stood on the lawn in front of the president’s house at the College of William and Mary with a group of undergraduates, fellow graduate students, and faculty singing the alma mater and wondering if anybody was hearing the students’ voices swell. That candlelight vigil took place within days of former President Gene Nichol’s announcement that the College’s Board of Visitors had not renewed his contract. The reasons for this remain as murky now as they did four years ago but have often been chalked up to personality clashes, a lack of fund-raising, or simply an inability to get along with Old Virginia.

Memories of Nichol have, of course, arisen during the two weeks following University of Virginia President Teresa Sullivan’s forced resignation by the Board of Visitors. Like Sullivan, Nichol had been extremely popular with students, faculty and alumni, made efforts to advance scholarship even in subjects that were not profitable to the university, and worked to increase student and faculty diversity at a school that often, how shall we say, completely lacked it. Like UVA Rector Helen Dragas’s comments, those from W&M Rector Michael Powell (yes, the one from the FCC, and yes, the one who is Colin Powell’s son) seemed inadequate to those seeking any explanation for the Board’s decision.

I attended a Board forum then with professors and students, and Powell’s statements seemed, like Dragas’s, bizarre. When fielding a question about why the Board had not immediately issued a statement (Nichol waited until two days after the notification of his effective termination to go public, citing a desire for the Board to let students, faculty, and alumni know themselves), Powell stumbled over an answer that, in essence, said, “;We needed to consult some lawyers to find the right language.” The Rector, along with two-thirds of that Board, was a lawyer. His explanation of the decision through invocation of rhetoric about “;tough decisions you may understand when you’re older” seemed to the undergraduates I spoke to like a “;When you grow up, you’ll understand how the big kids operate” statement, not the detailed explanation young adults at an elite university wanted to hear. Like UVA’s controversy will, William and Mary’s eventually blew over, with the installation of an interim-cum-full time internal president and a return to some semblance of normalcy. Nichol now serves as a named-full professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law.

So why drone on about this memory in a GradHacker post?

Because, as Marie Griffith pointed out in her excellent Religion and Politics piece, this story is not about the University of Virginia or the College of William and Mary. It’s about institutional cultures and academic politics.

As first-year graduate students, my peers and I reacted mostly with cynicism to the Nichol debacle. What was the point, we wondered, of studying to be historians if the humanities were worthless when compared with business interests? What would happen to us (and our stipends!) if we joined our tenured faculty members in striking and refusing to teach class until a resolution occurred? What would happen if we didn’t? Should we give an answer to the undergraduates who demand that we show our commitment to the university by continuing to teach despite the circumstances — or the ones who demand that we vacate our posts as a sign of that commitment? What was happening to the university system that we’d recently dedicated our lives to joining?

Four years later, we’re still engaged in many of those conversations. University structures are constantly changing. What will they look like in the two years until we look for professions within them, never mind the decades it could take to become entrenched?

We don’t, of course, have the luxury of waiting to ponder those questions and begin thinking about our responses and strategies for political situations beyond our control. That the era of the absent-minded professor is giving way to the clued-in and world-savvy one is not necessarily tragic. It’s important to think about giving students and parents something of tangible value for the financial investments they make. It’s important, too, to recognize that many humanities fields may hold intrinsic value and improve reading, writing, and critical thinking skills even when their factual basis seems detached from reality. It is often difficult to explain this to business or outcome-oriented individuals—the types of folks who mostly populate university boards — but it’s important to have those explanations prepared.

My friends and I decided to go about our normal business, wearing Nichol support pins and attending rallies and meetings when we could. Some professors' graduate students cancelled classes; others (particularly assistants and recent associates) and forged ahead after sending their classes e-mail notifications that attendance would not count and conscientious objection was applauded (leading, of course, to benefits for those who conscientiously objected to sitting in an indoor classroom during a beautiful spring day).

Ultimately, I think many of us wound up glad that we’d received a certificate in University Politics 101 so early during our careers. We benefitted from watching our department scramble to react and learned about the balance between academic freedom and self-preservation.

I don’t know whether UVA students will say the same in a few years, but I’d love to hear the thoughts of any current students out there. Has anyone experienced this at other schools, and what did you learn? What does this say about the current state of universities and their political structures? What should we as potential university employees do to prepare for our careers? In the spirit of higher education, perhaps the best way to make sense of the Teresa Sullivan debacle is to seek a professional education for ourselves.

On the Failure of Legacy Governance at the University of Virginia

Make sure to check out: Inside Higher Ed | Blog U

Crises and controversies are almost always useful learning moments, including in the world of higher education. I’m learning much this week while observing a roiling debate about the de facto removal of the University of Virginia’s President (Teresa A. Sullivan) after a mere two years in her leadership position. I’ve also found this an interesting if uneasy affair to observe following much turmoil here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in AY 2010-2011 about the possible separation of my university from the University of Wisconsin System via a scheme deemed the New Badger Partnership. The New Badger Partnership involved the creation of whole host of needed flexibilities, as well as a separate Board of Trustees (the equivalent of the University of Virginia’s Board of Visitors). This too was a roiling debate, which intersected, unfortunately, with the turmoil generated by Governor Scott Walker’s proposal to remove collective bargaining rights from in the public sector. To cut a long story short, our chancellor (Carolyn “Biddy” Martin) resigned after being in her position for just under three years to move to Amherst College, a bittersweet move, no doubt, for someone with genuine affection for UW-Madison.

Being immersed in the middle of huge governance debates makes one sensitive to their destructive elements, but also what they help shed light on. In this entry, I’ll try and flag some key events and resources to track the unfolding of the University of Virginia controversy, but also stand back and draw a few lessons, especially with respect to the governance of US public research universities in an era of austerity.

The official statements about President Sullivan’s removal can be read here:

- Teresa Sullivan To Step Down Aug. 15 as U.Va. President (10 June)

- Full Text of Email Announcing Sullivan’s Stepping Down (10 June)

- Rector Dragas’ Remarks to VPs and Deans (10 June)

- Statement from Gov. McDonnell (10 June)

The decision was announced by Helen E. Dragas, Rector of the University of Virginia’s Board of Visitors. As noted on the University website:

The Board of Visitors is composed of sixteen voting and one ex-officio non-voting members appointed by the Governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia, subject to confirmation by the General Assembly, for terms of four years. In addition, at the first regular meeting of the second semester of the academic session each year, on recommendation of the Executive Committee, the Board of Visitors may appoint for a term of one year, a full-time student at the University of Virginia as a nonvoting member of the Board of Visitors. The Rector and Visitors serve as the corporate board for the University of Virginia, and are responsible for the long-term planning of the University. The Board approves the policies and budget of the University, and is entrusted with the preservation of the University’s many traditions, including the Honor System.

Link here for the MANUAL OF THE BOARD OF VISITORS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 2004 (rev February 23, 2012) for full details on the Board’s “powers and duties,” which includes appointing and removing the University’s President.

Yet, in less than one week, we’ve also seen:

- College chairs, program directors issue letter to “;protest” Sullivan’s resignation (13 June)

- Statements by Rector Dragas (13 June) and EVP/Provost John Simon and EVP/COO Michael Strine (14 June) stating that “The Board of Visitors’ action is resolute and authoritative” and “confidential” in nature

- News, via the Washington Post, that many of the reasons hinted at removing Sullivan were in fact flagged by Sullivan herself on 3 May in a frank and reflective strategy document

- The emergence of an online petition (Rector and the Board of Visitors of the University of Virginia: Reinstate Teresa Sullivan as President of the University of Virginia) with 1000+ signatures

- The emergence of a Facebook page, satirical website and Twitter feeds (e.g, http://twitter.com/RectorDrago) regarding the Board of Visitors, especially the board’s rector, Helen E. Dragas, and vice rector, Mark J. Kington.

- Discovery that the Board of Visitors’ “dodged” public notice law (14 June)

- Resignation of the Darden Foundation’s Board of Trustees (Peter Kiernan) (14 June), following the release of an email (10 June) exposing his involvement in this supposedly “confidential” matter

- A Faculty Senate rebuke of the Board of Visitors, including its “lack of confidence in the Rector, the Vice Rector, and the Board of Visitors” (14 June)

- News, via the Washington Post, that ‘Three members of U-Va. board were kept in dark about effort to oust Sullivan,’ that only three members of the executive committee of the Board were able to attend the meeting where the final decision was made, and that the Governor of Virginia was not accurately informed [lied to?] about the deliberative process within the Board

- Student Council’s Request to the Board of Visitors for “a full explanation of the events and circumstances surrounding the departure of President Teresa Sullivan” (15 June)

- Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell calls “for more dialogue between the University of Virginia’s faculty and governing board,” that his office should not be involved in Board of Visitor decisions, and that “;All I can tell you is that we have very qualified people that serve on these boards,” McDonnell said. “; … They’re really top-flight people. A lot of business people that have run major organizations. And these decisions are largely left up to the boards.” (15 June)

- Resolution of College Faculty of Arts and Sciences Steering Committee (15 June)

There is ample coverage about the process, and the issues, via this pre-programmed Google search, and these local Virginian news sites:

- The Cavalier Daily

- The Daily Progress

Twitter is a great resource as well if you use the #UVa or #Sullivan hashtags.

Now, after 11 years here in the US, just as I start to think I’ve figured this country and its higher education institutions out, I get sideswiped yet again. What is surprising about this case?

First, look at the occupations of the 16 members of this key governance unit that the current and most recent Governors have appointed. As the Washington Post also noted:

And most of the 16 voting members of the University of Virginia’s governing board of visitors have given campaign contributions to governors who appointed them. In some cases, donations added up to hundreds of thousands of dollars.

This is a patently unbalanced and inward-oriented board, drawing from a very narrow segment of society. Given this approach to sourcing Board members, the capacity for group think, and an inability to reflect on the larger extra-Virginian context (including outside the US), cannot help but be limited. The homogeneous nature of the Board of Visitors arguably helps to explain how ineffective they are in handling this issue, and understanding how organizations like universities actually function.

Second, and on a related note, where are the faculty and staff voices on this Board? All we see are alumni (almost all business people, doctors and lawyers) and one “full-time student at the University of Virginia as a nonvoting member.” Even the heavily debated Board of Trustees being considered here at UW-Madison was to have 11 members appointed by the Governor, with the remaining 10 members representing multiple UW-Madison constituencies (faculty, staff, classified staff, alumni, tech transfer).

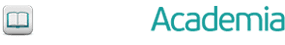

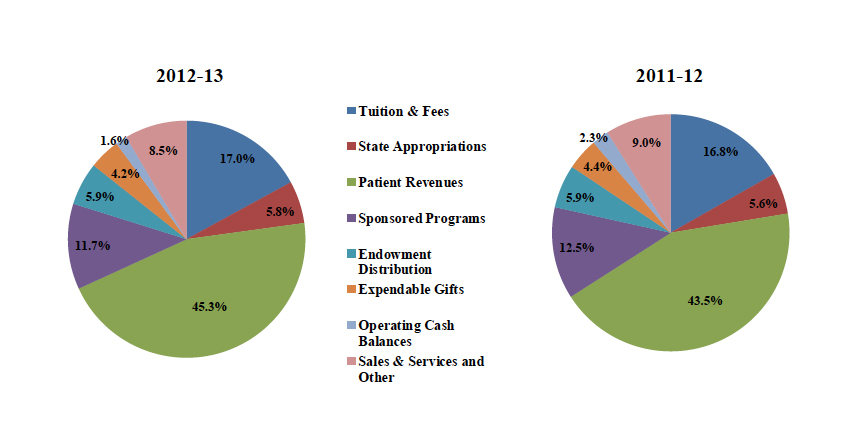

Third, there is a huge and still growing gap between declining level of public funding for public higher education in the US and the desire of state governments to maintain if not increase their governing power. In the case of the University of Virginia, for example, see these figures (and note the dark red element which is State Appropriations):

Figure 1: SOURCES FOR THE CONSOLIDATED OPERATING EXPENDITURE BUDGET (Source: University of Virginia, 2012-2013 Budget Summary All Divisions)

Figure 2: SOURCES FOR THE ACADEMIC DIVISION OPERATING EXPENDITURE BUDGET (Source: University of Virginia, 2012-2013 Budget Summary All Divisions)

These are important yet very limited proportions of revenue, and they’re not likely to get any larger in the long run. The austerity approach to higher education, so evident in many US states, clearly rules in Virginia. As the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia noted, in July 2011:

Five consecutive years of general fund (state tax revenue) budget reductions have put the affordability and accessibility of Virginia’s nationally acclaimed system of public higher education at risk. Measurements of the student cost share of education and the cost as a percentage of per capita disposable income at Virginia institutions are both at record high levels (least affordable).

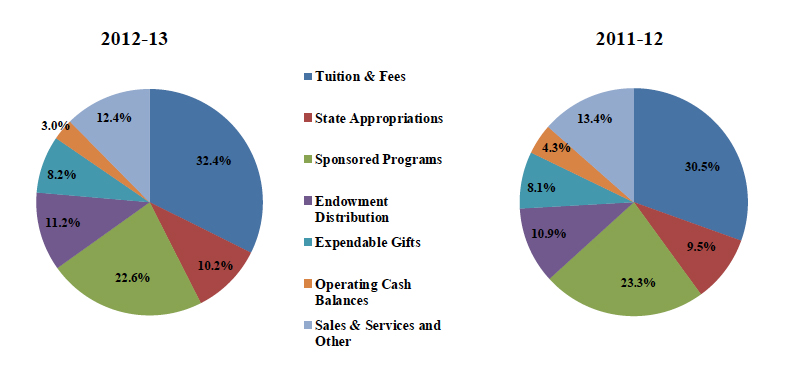

This is also a question that needs to be flagged at the national scale in the US, as is evident in this State Higher Education Executive Officers (SHEEO) figure:

Taking Care of (Administrative) Business

In academia, the summer break inevitably leads every professor to confront the very tasks he/she has put aside during the busy semesters of teaching: finish that research project; complete that journal article or book; catch up on more readings of favorite authors; brush up that syllabus; weed/add class materials, etc. To many, summer is really not a breather of one’s academic self, but merely a dedicated time to concentrate on things other than teaching. Except for the shorter library and office hours, and the minuscule number of students roaming about campus, summer is business as usual to many of us whose work follows wherever one goes.

My May summer vacation is different only in one regard from my regular semester: I am in the United States rather than my post in Iloilo City, Philippines. Although labeled as “;official travel”, in actuality I am running my Division’s affairs as Chairperson from wherever I can get access to the Internet. Since landing, I have written letters of all sorts– requests, endorsements, explanations, justifications, committee appointments, reports– to my bosses bearing electronic signature (which, fortunately for me, the Dean and University officials accept as official). Remotely, I arranged for our Division to conduct a series of training with employees of the Department of Social Welfare and Development; part of our extension activity. I advertised, received applications and arranged to hire substitutes and lecturers for the first semester, which begins in June 1. From whatever convenient desk I can open my laptop, I troubleshoot on course offerings and faculty loads- answering distress missives from the College Secretary about needing to open more General Education sections for incoming freshmen, a new recruit who suddenly pulled out because of legal encumbrance from her current University affiliation, and a faculty member who asked to defer going on study leave the last minute. Not even the 12 to 15 hour time difference could absolve me from delivering timely advisories to colleagues who are returning from or about to go on prolonged leaves of absence (for graduate studies or sabbatical). With email, one never really has time off; not even if one is 9,000 miles away.

Summertime is also a period of deadlines for research project proposals or travel grants. Therefore, if I wish to do something productive in the next calendar year (which begins June 1), I must turn in my applications during the summer. The writing and accomplishing of forms needed at home had to be wisely interspersed with sightseeing and visiting family and friends. Electronic connectedness, while a bane to my existence as Division chair is also a blessing if I were to turn in proposals in time. Another plus is that I am able to supervise a team of field researchers back in the Philippines through Skype. I have never appreciated electronic bank transfers until now; and the power of Google voice which allows me to place relatively cheap international phone calls to the Philippines.

But alas, the writing break which I sought and planned to use to anchor my summer days has long since disappeared from sight. Except for the two full days spent slogging over materials at the Library of Congress last weekend and yesterday getting my bearings at my University of Maryland College Park Library, I have not made progress on the writing bit. The pile of books (marked for relevant chapters) at my UMD office stares at me with alarm, asking, “;why haven’t you read me?” Just like a colleague at Johns Hopkins who similarly laments having not done any writing since he took a 4-month sabbatical, I am inevitably torn between doing my job and fulfilling life goals.

Iloilo, Philippines

Rosalie Arcala Hall is a Professor at the University of the Philippines Visayas and a founding member of the editorial collective at University of Venus.

Read More: Inside Higher Ed | Blog U

Thoughts on Romney and Higher Ed

At least hes not mandating creationism.

Mitt Romneys plans for higher education hence far are silly, but not catastrophic. Currently that puts him ahead of much of his party. .

It was not often hence. There was once a time — not all that lengthy ago, truly — when Republicans took public larger education seriously. The SUNY system never ever had a greater good friend than Nelson Rockefeller, for instance. The University of California program even survived two terms of Governor Ronald Reagan, despite occasional snipes about hippies. .

And that tends to make sense. As conservatives, their burden involved squaring arbitrary economic outcomes with a common cultural sense of the worth of fair play. Education provided a nice way to thread that political needle. The intelligent and driven kid who was born poor could work challenging in a public method and operate his way into the middle class and above. As long as that was correct, individuals on leading could plausibly claim that the total technique is fair, even if they just take place to be a entire great deal wealthier than absolutely everyone else. As extended as the economic hierarchy was at least open to a thing like meritocratic striving, those who have been left out could be blamed for their very own fate.

Over the previous decade or so, though, Republicans — as opposed to conservatives, which they are not any more in any meaningful sense — have shifted their position. Now they&rsquore openly hostile to increased education, except in for-profit kind. Rick Santorum&rsquos “what a snob!&rdquo comment, for all of its artlessness, fairly considerably encapsulated the id of the party in its current form. (The same could be said of Santorum typically.) Some of that is the lingering residue of hippie-bashing, but the latest surge in stridency can&rsquot be explained that way. (I don&rsquot recall a hippie resurgence in 2010.) I consider it goes a tiny deeper than that.

The increased education landscape in its current kind represents a direct disproof of the core of Republican ideology. That&rsquos why they hate it so considerably. It reminds them of the conservatism they left behind.

Please read more here: Within Larger Ed | Weblog U

The Up coming Chapter for HBCUs: Three Imperatives

There has been plenty of speculation about the long term of HBCUs. While some of this has played out in the media, there is also an on-going conversation within this sector about what needs to take place to make sure a viable and productive long term. Both conversations are delicate in nature, saturated with nuance and divergent views concerning which directions are very best. There are, nonetheless, a couple of clear environmental indicators that demand the focus of absolutely everyone concerning the long term of HBCUs regardless of 1&rsquos existing place.

one. Outcomes represent the &ldquocoin of the realm&rdquo: It is challenging to have a conversation about larger education right now without the national degree completion agenda becoming a part of the discussion.  Federal and state legislators have tuned-in and the accreditation community has upped the ante on the type of proof essential for demonstrating student learning outcomes.  The point is that institutional effectiveness and import are a lot more closely tied to the percentage of college students who graduate.  There does not look to be an exemption in the two or 4-year sector for institutions committed to serving poor, underrepresented, initial-generation school college students who face significant hurdles on the way to commencement. Innovation and fine-tuned institutional operations aimed at enhancing student results are no longer negotiable.

two. Delivery systems matter: Enrollment trends have essential financial implications for the viability of most HBCUs. There is now staunch competition for students from all geographic regions and for people with varying academic profiles.  There is no organic draw and accessibility matters in different approaches nowadays than it has in prior years. Past just getting admitted is the question of whether or not programs and degree programs are delivered in techniques that meet the requirements of nowadays&rsquos college students.  Two of the top 5 institutions producing the highest quantity of African-American baccalaureates are for-profit institutions. I have to feel that this is a result of non-conventional delivery techniques that make them accessible, thereby attractive to a sizable population of underrepresented students in search of an chance to earn a degree.

three. Utilizing data and evaluation to inform selections: As obvious as this could appear, increased education, as an enterprise, has not done a specifically good occupation at systematically collecting data about student functionality.  I am occasionally surprised by the truth that the same campus that boasts about its award-winning perform on the human genome is aware of virtually absolutely nothing about the effectiveness of a program intended to enhance persistence amongst STEM majors.  Traditionally, understanding outcomes have been assumed and the blame for failure has been assigned to college students only. The ability to systemically manufacture sophisticated actionable intelligence about student good results relative to institutional polices and practice is the new gold in greater education.

To be confident, these aspects are in play for all institutions. HBCUs, nonetheless, do not necessarily get pleasure from the luxury of delaying a response to them. And, the simple fact that there is practically nothing to stop them from being on the frontier is fascinating. These environmental elements represent the stage on which the subsequent chapter for HBCUs will play out. The value of HBCUs can not be overstated for the duration of a time when the nation is worried about whether it can create adequate graduates to satisfy workforce demands. Consequently, the up coming chapter will not be about whether these institutions are nevertheless appropriate but how they will make a greater contribution to the nation&rsquos greater education agenda.

My Program Policies

In a previous posting on “;unteachable students” I included a brief portion of my course policies document from one of my composition classes where I use a Q&A style format to try to give context to the content and practices of the course.

Surprisingly, and to my mind, strangely, there was a fair bit of interest in this, maybe more than the larger message of the posting itself, so I’ve been convinced to include a fuller example of this kind of course policy document.

Some disclaimers:

1. I make no warrants that this is a good way to do things. Though I do have fourteen years of classroom experience, and often read critical work in literature, composition, and creative writing pedagogy, I am no expert. What I do seems to work for me. Your mileage may vary.

2. I’m posting this in the interests of discussion, not to demonstrate my non-existent expertise. The development of my own practices and policies is an ongoing and ever-evolving process drawn not just from my experience, but from the knowledge and experience of others. The DNA of previous teachers and colleagues is all over this thing. I’m very interested in hearing from others how they tackle these issues.

3. I expect that some things I have to say will meet with some disagreement. Again, I would like to hear about different approaches, but the idea of us arguing with each other about who is doing it “;right” and who is doing it “;wrong” is completely uninteresting to me, and probably others.

4. The other post included material from a composition course. Because I still teach that course, and I don’t want my entire policies searchable on the Internet, I’m using one developed for a literature course that I’m unlikely to teach in the future. My hope is that the principles behind it are the same.

5. I’ve offered additional comments and annotations here and there in italics, led by my initials, JW.

6. This document is actually the basis for the first day discussion/activity for the course. At the start of class, I hand out the questions to the students, and they ask them in order. It’s goofy, but sort of fun. I usually speak extemporaneously, rather than reciting the text verbatim from the document, though the content is the same. They print off and read this document after the first class as a reinforcement of the material.

7. It’s very long, and possibly quite boring. Proceed at your own risk.

—

English 215: Contemporary Literature

JW: Boilerplate about sections and times and office hours removed for the sake of space. I also haven’t included the specific reading list because I changed it every time.

Frequently Asked Questions about English 215

Q: Who are you?

A: As the top of the syllabus notes my name is John Warner, and I am a native of Northbrook, IL, a northern suburb of Chicago, that is forever immortalized in the great John Hughes movies of the 1980’s (Sixteen Candles, Breakfast Club, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, etc…). I graduated from the University of Illinois in 1992 with a degree in Rhetoric, which is really just a fancy name for “;writing.” After a couple of years of work in Chicago, I returned to graduate school at McNeese St. University (go Cowboys) in Lake Charles, LA, where I graduated with two degrees, an M.F.A. in Creative Writing and an M.A. in English Literature in 1997. In addition to teaching I am a writer and have published several books and dozens of articles and stories. I also work as an editor of a daily humor-oriented website called McSweeney’s Internet Tendency (www.mcsweeneys.net).

This is my sixth year at Clemson, and while here I’ve taught writing and literature courses of all shapes and sizes. Prior to coming to Clemson I taught at the University of Illinois and Virginia Tech.

I am an Aries and enjoy long walks in the sand.

JW: As previously noted, I no longer work at Clemson. I include this background information because I want my students to be thinking about me as a specific human being (albeit of a teacher-type), rather than generic “;professor.” I also use it to establish my “;credentials” to teach the course. During discussion of this question during class, I often have fun making them guess what state McNeese St. is in. It usually takes a good 20 tries. The final line about “;long walks in the sand” is a joke, and at the time, I’d never taken a long walk in the sand. I’ve since moved to a place proximate to beaches and do so at least once a week, and it turns out, I really do enjoy them.

Please read more here: Inside Higher Ed | Blog U